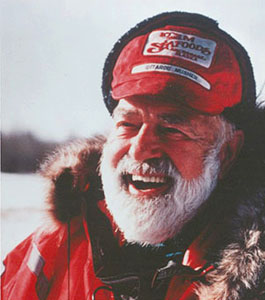

Colonel Norman Vaughan

American Polar Society Luminary

Colonel Vaughan began his polar career as a volunteer with the Wilfred Grenfell Medical Mission in Labrador in 1925, where he delivered medical supplies and performed medical evacuations by dogsled. Dog mushing was a significant part of Vaughan’s life from that time forward.

Colonel Vaughan began his polar career as a volunteer with the Wilfred Grenfell Medical Mission in Labrador in 1925, where he delivered medical supplies and performed medical evacuations by dogsled. Dog mushing was a significant part of Vaughan’s life from that time forward.

Vaughan dropped out of Harvard University to become a dog driver for the First Byrd Antarctic Expedition (1928-1930). He and Arthur T. Walden, head of the dog department, with their teams supported Admiral Byrd and others on skis to scout the site for their Antarctic base (“Little America”), thus becoming the first Americans to drive dogs in the Antarctic. More importantly, Vaughan was the lead dog driver for the 1,500-mile six-man geological party, headed by Dr. Laurence Gould, geologist and Byrd’s second-in-command, which traveled up the Ross Glacier, and then first explored areas in Marie Byrd Land and along the base of the Queen Maud Mountains. Soon after the expedition, in 1932, Vaughan competed in the Dog Racing event in the 1932 Olympics.

Wartime activities utilized his dog driving expertise. In 1942, during World War II, Norman Vaughan arrived with his six dogs aboard the USCGC Comanche to retrieve one of the two crashed B-17’s Norden bombsites from the 8-plane “Lost Squadron”; USNR LTjg Freddy Crockett (also a dog driver on Byrd’s First Expedition) with his dog teams had just rescued the 25 aviators from the ice who had gone down with the planes. (Later, from 1981 to 1992, Norman Vaughan returned to Greenland each summer to help locate all of the eight downed planes frozen under the ice; he also helped recover one of the “Lost Squadron” aircraft — the P-38, named “Glacier Girl”– which has since been restored and flown.) By 1943, the effort to utilize dogs for war purposes was shifted to command of Colonel Vaughan, North Atlantic Wing, Air Transport Command, Army Air Corp. He trained and equipped the search-and-rescue sled dog units to retrieve pilots and cargo from crashed aircraft. By the end of the war, at least 100 downed pilots were recovered.

In 1945, as the Battle of the Bulge was being fought and heavy snows blanketed the Western Front, Col. Vaughan argued for a month that dogs were the only transport that could rescue and return the wounded to the rear of the battle for medical treatment. Finally, General Patton issued the order “Send in the dogs.”

With impressive coordination, Vaughan quickly assembled 17 drivers and 209 dogs to a training camp in Maine, then deployed them to France. Because of administrative delays, the dogs did not arrive before the snows melted and so did not participate in the Battle; however, the operation proved the ease with which dog teams could be assembled and dispersed whenever the need arose. Dogs were used in this way until helicopters realized their full potential in the 1950’s and took over those functions. Later, beginning at age 72, he participated in thirteen 1100-mile long Iditarod sled dog races in Alaska, where his last finish was in 1990 at the age of 84.

10,302′ Mount Vaughan, Antarctica

The APS would like to express its gratitude to Capt. Donald M. Taub, USGS (Ret) for contributing testimonial information that has been incorporated in the revised biography above. Additional sources include: Col. Vaughan’s website, National Geographic, National Public Radio, Byrd’s Little America, Gould’s Cold, the story of the P-38 “Glacier Girl” and her eventual recovery, and War Dogs: A History of Loyalty and Heroism by Michael G. Lemish. We also thank Merlyn Paine for her research and preparation of the above narrative.